What is ‘Critical Habitat’?

There is a great deal of confusion surrounding what Critical Habitat is – as well as how it is defined in legislation and applied in practice – so, right out of the gate, we want to clarify that Critical Habitat (capital ‘C,’ capital ‘H’) is a legal term with a specific definition.

It is distinct from habitat that is referred to as key, important or crucial. Even the expression ‘habitat that is critical’ does not necessarily refer to area that is legally Critical Habitat, if ‘critical’ is being used descriptively as opposed to technically.

With that said, the legal definition of Critical Habitat is found in the Species at Risk Act. The Species at Risk Act (SARA) recognizes that habitat protection is needed to prevent wildlife species from becoming extinct. SARA defines Critical Habitat as “the habitat that is necessary for the survival or recovery of a listed wildlife species and that is identified as the species’ critical habitat in the recovery strategy or in an action plan for the species.”

When a species is first listed under the act, a process of identifying the Critical Habitat for the species is carried out by the Federal Government in partnership with the relevant provincial government(s). Once Critical Habitat has been formally identified, measures are put in place to prevent the destruction of that habitat.

Under SARA, it is illegal to destroy any part of the Critical Habitat of a listed species. A ‘Critical Habitat Order’ is the legal mechanism that formally prohibits Critical Habitat destruction.

How is Critical Habitat Defined?

With the vast majority of listed Species at Risk, Critical Habitat is an explicitly bounded geographical area (from waypoint to waypoint). There is little to no room for ambiguity, because the area contained within the defined boundaries is automatically considered and treated as Critical Habitat. This approach makes it very clear which areas should be avoided by impactful activities.

Here’s the rub: How Critical Habitat is defined and applied for the bull trout – in addition to the Westslope cutthroat trout – is not the same as how it is for most other listed Species at Risk.

In the past few years, there has been a trend toward using what is called a “bounding box” definition of Critical Habitat (described below) when federal Recovery Strategies are created.

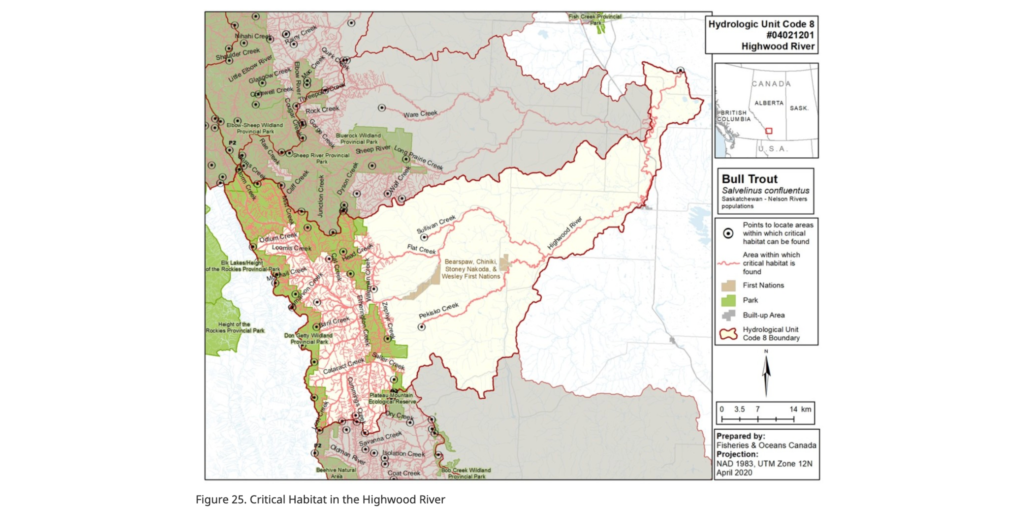

In the case of bull trout, the 2020 Recovery Strategy identifies the “area within which critical habitat is found” in detailed maps, including throughout the Upper Highwood watershed. The ‘Critical Habitat Order’ prohibits “the destruction of any part of the critical habitat of the Bull Trout that is identified in the recovery strategy for the species”.

The Critical Habitat Order further describes the identified Critical Habitat and includes riparian buffers:

“The critical habitat identified in the recovery strategy includes parts of the Oldman, Bow, Red Deer, and North Saskatchewan river basins in southwestern Alberta. The recovery strategy identifies the critical habitat of the Bull Trout as clean, cold waters that tend to be structurally diverse (complex habitat), well connected, contain areas of groundwater upwelling, and offer protection against high or low stream flows, disruption of the stream bed, fine sediments, high water temperatures, freezing to the stream bed, and the loss of pools and cover. Maps of the areas that contain critical habitat can be found in the recovery strategy. Only those areas within the identified geographical boundaries possessing features and attributes necessary to support defined life stage functions comprise the critical habitat. A width of 30 m from the high water mark on both stream banks is included in the identified critical habitat. This 30 m riparian area is necessary to protect key stream attributes such as clean and cold water with low sediment and silt, maintain channel configuration and habitat structure, and provide terrestrial food inputs and woody debris into the aquatic environment.”

A note on riparian buffers: For native trout species, the recovery strategies identify 30-metre riparian buffer zones extending from the high-water mark as critical habitat. Based on the summary of literature, including that which the Government of Alberta carried out in drafting the provincial recovery plan, a significant amount of evidence suggests that this is insufficient to protect from the impacts of sedimentation.

This was described in the DRAFT Alberta Bull Trout Recovery Plan, but not included in the final version. For Westslope Cutthroat Trout, a species with similar habitat requirements, DFO originally included a more precautionary 100 m riparian buffer in the draft Federal plan, which Alberta officials questioned – leading to the 30 m buffer being used.

How does the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO) Interpret Critical Habitat?

To fulfill the objectives of the Recovery Strategy all the identified “area within which critical habitat is found,” should be legally considered Critical Habitat and protected from damage. This approach makes ecological sense, as land-uses and associated disturbances outside the areas of occupancy or areas identified by the bounding box approach can impact habitat conditions within these areas. This is particularly relevant for areas upstream that could impact habitat conditions and attributes downstream.

However, the DFO – the relevant Federal authority in the case of bull trout and other aquatic species at risk – takes a different approach and uses what’s known as a ‘bounding box’ over a stream segment (or entirety of a stream), which delineates a geographical area within which potential Critical Habitat is found.

Areas within the bounding box are required to have certain habitat features, functions, and attributes demonstrated to be present through on-site assessment before they are actually protected as Critical Habitat. As a result, it does not mean that an entire watercourse or system found in a Recovery Plan is automatically protected as Critical Habitat.

This is described in the definition above: “Only those areas within the identified geographical boundaries possessing features and attributes necessary to support defined life stage functions comprise the critical habitat.”

How Does this Work in Practice?

As a result of the ambiguity in defining Critical Habitat in the Recovery Strategy, DFO expects industry to identify if the characteristics of Critical Habitat as outlined in the Recovery Strategy are present in areas where work is planned. If industry thinks that an area identified as “Potential Critical Habitat” meets the criteria, then they apply for a permit from DFO.

If they don’t apply for a permit when they should have done, they can be subject to enforcement measures. But, by this time, the damage has already been done. With few DFO enforcement officers on the ground, this often leaves concerned members of the public to have to bring forward problematic cases.

According to the current approach to implementation, it is the company’s responsibility to identify if an area meets the characteristics of Critical Habitat – however, it is not up to the company to determine whether an area is at risk of damage or destruction. Application for a SARA permit is the avenue for DFO to assess whether the risk or damage is acceptable within the context of species recovery.

Following our coverage of the lack of permits Spray Lake Sawmills had in place to build a bridge over the Highwood River, many people pointed us to the above map (Figure 25), noting that the Highwood River is listed critical habitat. And this is how it should be applied. However, due to the nature of how Critical Habitat is defined in the Bull Trout Recovery Plan and interpreted by the DFO, it is only an area within which Critical Habitat is found – and is not automatically treated as such, unless industry or the relevant project proponent assesses it to be Critical Habitat. However, based on public comments from Spray Lakes Sawmills, it does not appear that they even conducted the on-site assessment to determine whether it constitutes Critical Habitat.

Please note: We have both written and verbal confirmation, from multiple sources at the DFO that the Critical Habitat assessment is completed by industry who then applies for a permit to DFO.

As previously mentioned, CPAWS believes that the entire area identified as potential Critical Habitat should be legally protected as Critical Habitat.

The approach currently taken by DFO reduces accountability and, in some cases, could create an incentive for companies to report that an area lacks the features to be Critical Habitat. It also adds unnecessary complexity. And, by failing to adhere to a precautionary principle, damage can and does occur to Critical Habitat without DFO’s (or the public’s) prior knowledge.

Furthermore, stream habitat is very dynamic and so the specific location of the habitat attributes described above will change over time. Instream habitat usage will vary depending on changing conditions over short timescales. Watercourses are also influenced by tributaries which are connected to and contribute to habitat conditions in mainstream waterways, and thus should be protected as Critical Habitat.

This means that the only reasonable way to define Critical Habitat is to include all of the identified watercourses in the Recovery Plans and their associated riparian edges.

What’s the Solution?

The solution is simple – use the common-sense precautionary definitions that have been provided in the Recovery Strategy – all watercourses listed as an “area within which Critical Habitat is found”, should be considered Critical Habitat and legally protected against damage and destruction. After all, within a watershed, each of the identified rivers, streams, and creeks are all part of the same interconnected systems of habitat that our native trout species rely on.

All Photo Credit: Amber Toner | @TheBugParade on Instagram

More Blog Posts

Fortress Mountain Resort: An Amusement Park in our Wilderness

Speak Up, Write Out: The Power of a Local Op-Ed